By Akers Editorial

Carrying the legacy

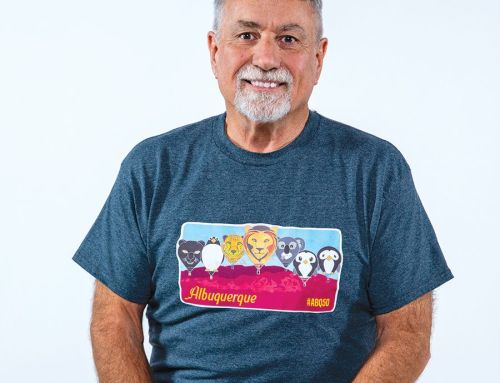

Sculptor J. Michael Wilson grew up a long way from Florida, but his lifelike bronze statues at the Brownwood entrance of The Villages skillfully capture the history of Florida’s whip-cracking, cattle-driving cowboys.

story: Mary Ann DeSantis photos: Fred Lopez+Liz Tidwell

A cattle drive along State Road 44 at the entrance of The Villages’ newest town square, Brownwood, is an unexpected scene that has passersby regularly stopping for photos. The bronze statues depict a scene from Florida’s rugged past when hard-working cowboys traversed this area long before it became ‘America’s Friendliest Hometown.’ And if the 12 bronze steer seem a bit malnourished, it’s with good reason. The Florida Frontier was anything but friendly.

“Florida had elements that weren’t easy for cowboys to deal with,” says sculptor J. Michael Wilson, who lives in Alpine, Utah. “They didn’t have green, lush pastures where the cattle stood around grazing.”

Wilson knows animals and he has been accurately capturing their likenesses — and their personalities — for more than 30 years. His bronze creations have a lifelike aura that comes from his first-hand knowledge. Wilson started out studying animal science at California Polytechnic University with plans to become a veterinarian.

“It didn’t take too many labs before I knew I was in the wrong field,” he remembers. “Any situation that involved blood, I would black out on the floor. After the third year, I knew I needed to rethink my career choice.”

He believes dropping out of school was a huge disappointment to his parents, and it was also a hard time for him as he tried to figure out what he wanted to do. He worked on a horse farm, which he says helped him learn about the personalities of animals. A few months later, he and a friend began a construction business, which gave Wilson the time to pursue art classes at a community college in Mission Viejo, Calif.

“It quickly became obvious to me how much I loved sculpting,” he says. “It took two years to do my first horse sculpture.”

That sculpture was selected to represent the U.S. at the first International Art Exhibition, where the president of the American University in Rome saw it and invited Wilson to apprentice with sculptor Albert Friscia in Rome, Italy.

“Friscia taught me how an artist lives his life,” he says. In 1982, Wilson returned home and made the commitment to become a professional sculptor.

The following year, his career launched into the big time when he received the commission to create a life-size horse and rider statue for the 1984 Summer Olympic Games in Los Angeles. The night before the Olympics began, Wilson was invited to present a miniature version of Victory’s Gate to Britain’s Royal Highness Prince Phillip, an event that his father was able to witness.

“That night meant so much because my dad was there. During the time I was working on the sculpture my mom passed away, but she got to see the clay model,” Wilson remembers. “I think that commission made up for the disappointment my parents must have felt when I dropped out of college.”

Other commissions followed, including one to sculpt the University of Southern California’s mascot Tommy Trojan on his horse Traveler, called Spirit of Troy. Wilson quickly became the go-to sculptor for equestrian-themed monuments. His talents, however, went far beyond horses. In 1990, the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences commissioned Wilson to sculpt the bust of American playwright Paddy Chayefsky. Since that time, Wilson has created seven more busts for the Academy’s Hall of Fame, including one of Tom Brokaw. In 1996, he was commissioned to do two 14-foot-tall, 18-karat gold-leafed Emmy sculptures that are permanently displayed in the Academy’s theater. In recent years, he has created two monumental bronze sculptures for the Colorado National Monument, including one of trail builder John Otto on horseback.

Adam Warner, who owns Mountain Trails Gallery in Park City, Utah, has known and represented Wilson for years. It was Warner who was first approached by The Villages to find a sculptor who could complete the Brownwood project within a year. Warner put together a specific proposal with Wilson in mind.

“Mike is so good not only because the anatomy of his sculptures is spot-on, but he also gives them realistic personalities,” says Warner. “When you look at his sculptures, you get a sense of whether the animal is ornery or gentle. Mike gets realism down with details but he makes the sculptures come to life — he’s the best at that.”

Indeed the Brownwood scene seems almost lifelike as the cattle are herded across the Brownwood entrance — the very land where Cracker cowboys once roamed. The bronze cowboy’s gritty yet gentle face reflects the determination it took to drive cattle across the state at a time when mosquitoes could ravage a herd and hurricanes popped up with no warning, except for distant dark clouds. The calf in his arms symbolizes the cowboy’s hope for the future and led to Wilson naming the installation Carrying the Legacy.

Both Warner and Wilson say that everyone involved in the project was committed to making the scene realistic and educational. In fact, both men said research was imperative before launching the project.

“I was unfamiliar with Andalusian steer, which were indigenous to the region. They are much smaller than longhorns,” explains Warner. “Mike did the research to make sure everything was correct.”

In November 2011, Wilson began making small models for the installation. The process included getting computer scans that would enlarge the forms into Styrofoam bases where Wilson would begin applying clay. As soon as he finished one piece, the Adonis Bronze Foundry would pick it up and he would continue with the next one. The project took about nine months — record time for a sculptor who is used to having a year or more to complete just one piece.

“I did not see all the pieces in bronze until the day they were loaded on the truck. That’s when I saw the animals’ personalities and how the sculptures would play off each other,” says Wilson. He was particularly struck by how much the dog looked like his own dog.

The sculptures are one-and-a-quarter life-size because Wilson says outdoor pieces need to be slightly larger than life. “It’s very different from a sculpture for someone’s home,” he explains. “The water tower and palm trees near the entrance would have dwarfed them.”

Wilson says creating the installation was one of the most enjoyable commissions he’s ever had in his 31 years as a sculptor. His first sketch — a cowboy carrying a small calf followed by the herd — was very similar to his final product.

“It’s not often your first concept drawing is accepted by a client,” the artist says. “Everyone was so accepting of my ideas and gave me a lot of freedom. When you work with a lot of people, it doesn’t always go that way. I can’t thank The Villages enough for such a great project.”