September 30, 2024

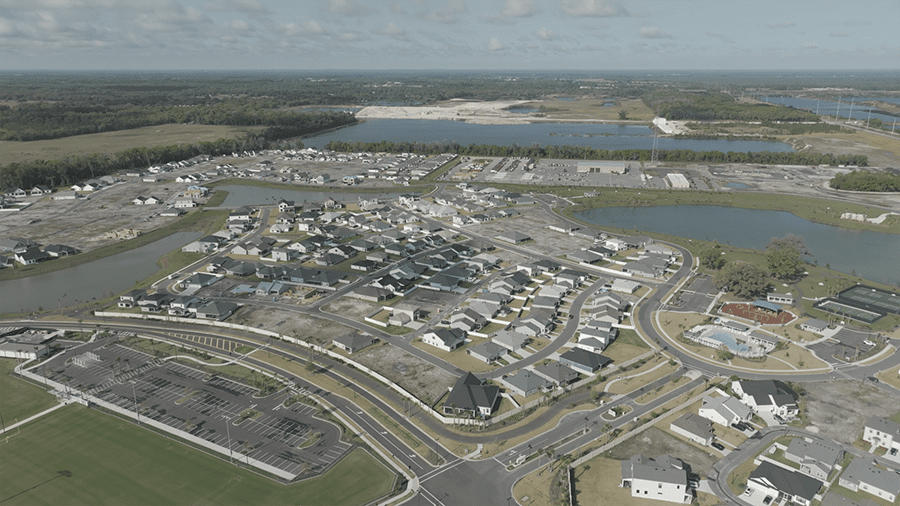

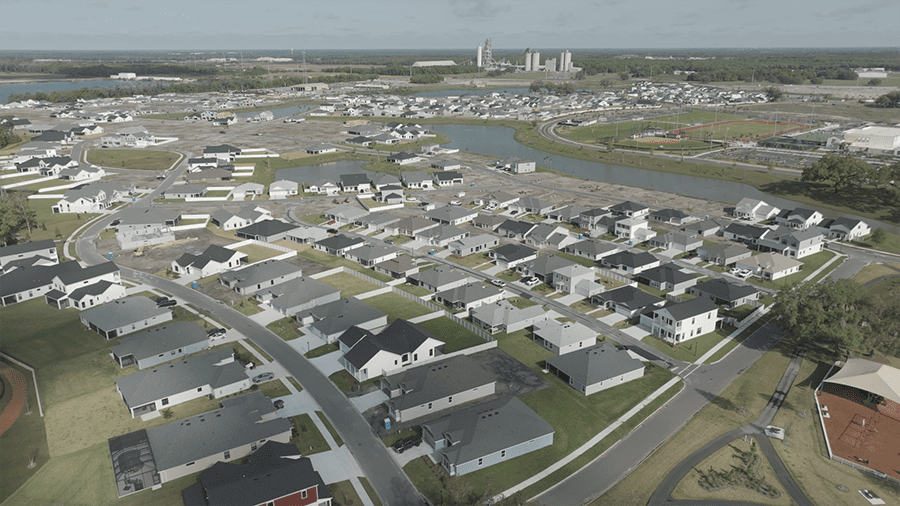

Growing Pains: Lake and Sumter Counties Continue to be Among the Fastest Growing in the State

By Akers Editorial

Growing Pains: Lake and Sumter Counties Continue to be Among the Fastest Growing in the State

Central Florida’s appeal is undeniable— it has quickly become a hot spot to live, work, and play. Unlike many other areas experiencing population decline, Florida is booming, with five of the nation’s fastest-growing metro areas calling it home. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, our region is a prime destination for Americans relocating to the South. Incredibly, 10 of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas from 2022 to 2023 are right here in our midst.

Wildwood/The Villages, in particular, has captured national attention, recently named the fastest-growing metro area in the U.S., with a 5% population increase. This surge is a testament to the area’s allure and the opportunities it presents. However, rapid growth brings its own set of challenges. Are we equipped to handle this influx?

To explore this, the Style team reached out to local officials to get the inside scoop on how our communities are adapting to this significant population surge. We investigated the ripple effects on schools, roads, the food supply, infrastructure and beyond. What we found is a landscape of both hurdles and prospects as our region evolves. As Central Florida continues to grow, it’s clear that we must adapt alongside it.

Breaking Ground: Navigating the complex path to new developments.

You can’t stop growth.

The old and often overused adage is especially true in Florida. Growth is literally written into our state statutes.

And with growth comes the need for more housing.

So, how does a new housing development get approved?

“It is surprisingly complex,” says Dan Miller, Leesburg’s planning and zoning director. “It takes a team of people from many different disciplines — infrastructure, zoning, the police, water, wastewater — all these different entities who are subject matter experts to come together to review a specific development to make sure that it will be constructed in the matter proposed and to the codes and statutes required.”

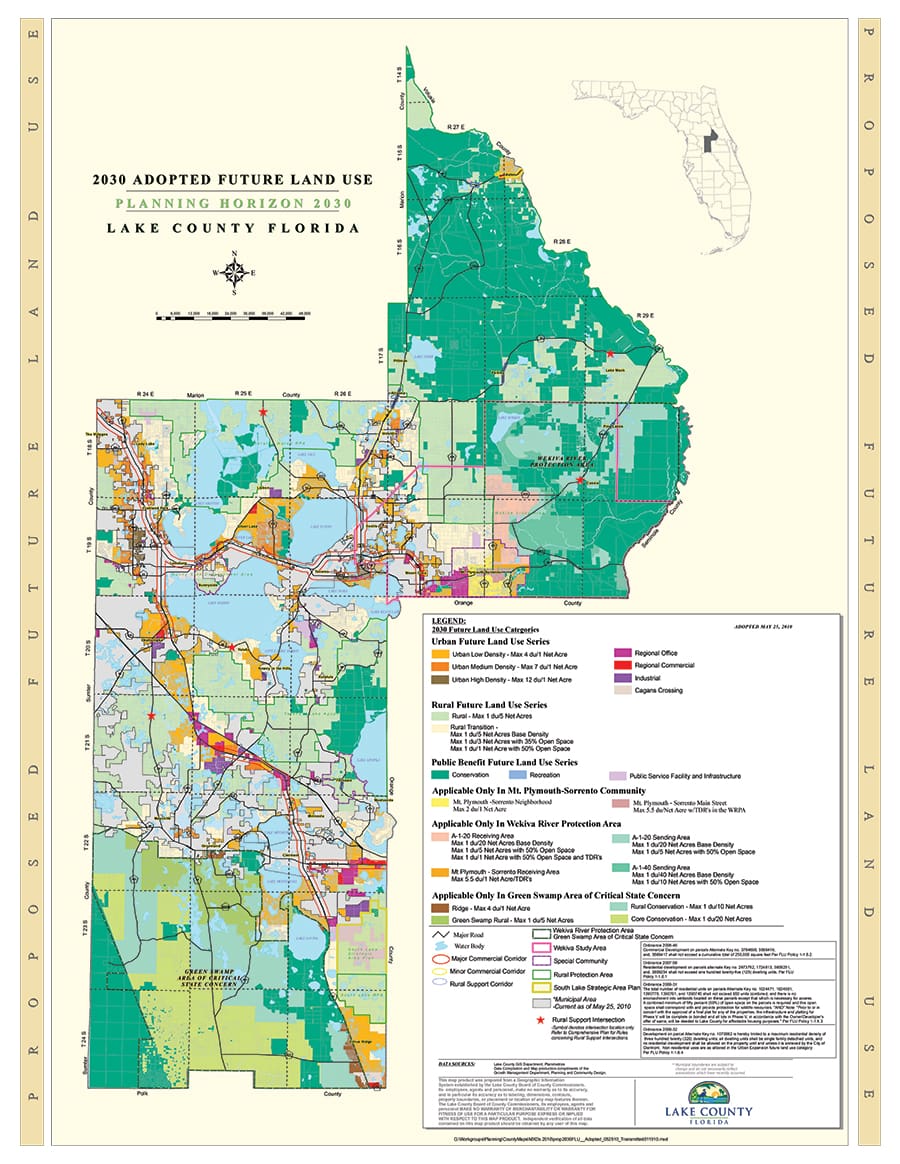

Plans and regulations

State statute requires municipalities to maintain comprehensive plans and land development regulations to manage their inevitable growth.

A comprehensive plan is essentially a growth guide for each city. According to Florida statutes, the plan “shall provide the principles, guidelines, standards, and strategies for the orderly and balanced future economic, social, physical, environmental, and fiscal development of the area that reflects community commitments to implement the plan and its elements.”

The plan includes a future land use map “designating proposed future general distribution, location, and extent of the uses of land for residential uses, commercial uses, industry, agriculture, recreation, conservation, education, public facilities, and other categories of the public and private uses of land,” the law says.

A municipality’s land development regulations include things like density and open space requirements, minimum lot sizes and setbacks and landscaping and signage guidelines.

Development processes may differ slightly from community to community, but the comprehensive plans and LDRs “are the guiding documents of the process upon which staff and external reviewers analyze the proposal,” says Lady Lake Growth Management Director Thad Carroll. “The applications must meet the requirements of both documents for approval.”

How the PUD process starts

Many of the housing developments we see popping up are planned unit developments, which Florida statutes define as “land that is planned and developed as a single entity or in approved stages with uses and structures substantially related to the character of the entire development, or a self-contained development in which the subdivision and zoning controls are applied to the project as a whole rather than to individual lots.”

Developers often design PUDs as interactive neighborhoods with a mix of housing, retail, office space and other amenities.

For example, Kolter’s Hammock Oaks in Lady Lake, adjacent to The Villages, is a PUD. The 732-acre project includes single-family homes, townhomes, apartments, retail space and a network of multi-use trails.

Carroll says the timeline from application to approval on a planned unit development can vary.

“The most important factor in how long the process may take is the responsiveness to comments regarding the application materials,” he says. “Obviously, the more time it takes the applicant to address comments, the longer it will take to get on a public hearing agenda.”

Carroll has seen applications in Lady Lake take over a year to get approved.

“Sometimes items are tabled because the Planning and Zoning Board or Town Commission need further clarification before making an informed vote,” he says. “Other times, it is simply a matter of the applicant not addressing staff comments in a timely manner.”

A pre-application meeting with the planning department is often the first step in the process in both Leesburg and Lady Lake.

These projects always include a zoning change because of the uniqueness of the PUD zoning category. Zoning determines the way land can be used for residential, commercial, industrial and agricultural uses.

In addition to a zoning change, PUD applications include a comprehensive plan amendment and, in some cases, annexation into the city. Documents in those applications include the site plan, zoning, flood, aerial and wetlands maps, the land’s legal description and more.

Planners aren’t the only ones who review these applications. They’re sent out to all the city departments for comments, Miller says.

“Police might say ‘we’re going to need to add an officer’ or ‘we can cover it,’” Miller says. “Same thing for water — ‘we have capacity’ or ‘our lines will not have capacity.’”

Lake County Schools also reviews PUD applications to determine the impacts on schools. And Lake County’s public works department often looks at applications to determine county road impacts, Carroll says. For developments in Lady Lake, The Villages Public Safety department is sometimes tapped to comment on potential effects of a proposed community.

Because of the volume of proposed developments in Leesburg, the city is running about 30 days per review, Miller says.

Once all comments are collected, they’re returned to the project engineer for changes. This could take a few days up to a couple months, depending on how responsive the engineer is. The revised plans then go out again. “You do that until all of the comments are responded to and corrected,” Miller says.

Typically, there are two or three rounds of departmental review, but some proposals take more, he adds.

Planners are tasked with ensuring the proposed development agrees with the municipality’s comprehensive plan and land development regulations. They make a recommendation based on that.

“It’s not based on ‘Does Dan like it?’ or ‘Does the staff like it?’” Miller says. “We’re not working on our personal opinions. It’s a professional recommendation based on codes and the comp plan.”

If a plan does not comply with the comp plan and LDRs, it requires a variance, which, if granted, gives the developer special permission for something outside of the code.

Next, the planning department’s recommendation is forwarded to the city’s planning commission and city commission.

Public meetings

Before an item reaches the planning commission, there are advertisement requirements that must be met.

Adjacent property owners are informed via mail two weeks before the scheduled planning meeting. And signs are posted on the pertinent property with information about the upcoming meeting. Florida law also requires meetings be advertised in newspapers.

Planning boards are volunteer-staffed. Leesburg’s Planning Commission has seven members. Lady Lake’s Planning & Zoning Board has five.

At each meeting, members review proposed plans, taking into account the city’s comprehensive plan and land development regulations, as well as the non-binding recommendation of the planning department. They then make a recommendation to the city commissioner. They do not make recommendations on annexations — those go straight to commissioners.

The planning commission also has the power to forward their recommendation to the city commission with more than just a yay or nay. For instance, with its approval recommendation, Leesburg’s planning commission also recommended that the Poe Road subdivision be required to plant a non-clumping bamboo buffer along the western property line that abuts a seven-acre residential property.

That piece of property is owned by a man who told the planning commission in May he was concerned about losing the natural feel of his land. On his daily walks, he relishes hearing the sounds of birds and bugs and seeing Florida native turkeys, bobcats, hogs and bears.

Plans for the Brightleaf community call for 135 single-family homes on 49 acres along Poe Road in northeast Leesburg. Fifteen of those homes will line the man’s property.

Miller agrees that the buffer was a good idea. “I would want the bamboo myself,” he told the commissioners at the meeting.

Just as planning department recommendations are not binding, neither is a recommendation from the planning commission. It’s forwarded to the city commission for their ultimate say.

At the city commission, each development has at least two hearings, a first and second reading.

The first reading is typically just that — a reading of the ordinance to introduce it without a vote. The second reading is where commissioners ask any questions of planning staff or the applicant, entertain any debate and hear from the public. Some of these meetings get particularly heated.

“Sometimes there’s absolutely no one,” Miller says. “And sometimes there’s a full house.”

Ultimately, the Leesburg City Commission approved the Poe Road PUD, which included annexation into the city. The plan also called for a natural buffer along the western property line.

In Leesburg, approved PUDs expire in four years if there has not been substantial commencement on the project, Miller says.

From approval, how long the development takes to be built depends on factors such as the developer, the scope of the project and the economy, specifically, the demand for that product, Miller says. A large project can take 10 years to be completed.

Denials, however, can get tricky, legally speaking. The constitution protects property owners’ rights and a taking of property can land a city in hot water. In this case, the taking would not be physical, but economic.

“As long as (the development is) within the code, it becomes very difficult to deny it because if you take away the economic value of that property, it is considered a taking,” Miller says.

Denying a PUD based on traffic alone is another no-no.

“That one is tough because traffic is one of if not the biggest issues that we have to deal with,” Miller says. “And the county and the state are really the drivers behind traffic improvements because most of the roads in Leesburg are owned by the county and state.”

Requiring a developer to provide something to the city outside of the reasonable scope of the development — like building a park across town — can also prompt legal action against a city. That’s called an exaction.

How the public can get involved

You don’t have to be an adjacent property owner to get involved in the development process.

“Residents can attend the public meetings, speak at those meetings, submit letters of support or opposition to project proposals, conduct their own research of the proposals via requesting application materials under a public record request, or even organize the local community to support or oppose the project, including social media campaigns,” Carroll says.

Miller says the No. 1 way people can get involved is to vote.

After all, the officials on your city, town and county commissions are the ones who make final decisions about development in our community.

“Get out and vote,” Miller says. “And I’m not leaning left, right, up or down. I’m saying voting is extremely important because elections have consequences.”