August 6, 2025

Inside Lake County’s Battle to Stop Fentanyl Before it Ends Another Life

By Roxanne Brown

Inside Lake County’s Battle to Stop Fentanyl Before it Ends Another Life

80,000. That’s how many Americans died from drug overdoses in a 12-month period ending November 2024, according to the CDC. In Florida alone, the toll was roughly 5,400.

Every one of those people had a name. A story. Family members who still wake up in the middle of the night, longing for someone who isn’t coming home.

Lake County Sheriff Office Capt. Ron Patton says the numbers are not only devastating, but alarming. “It’s not just happening in big cities. It’s happening right here,” he says. “Every overdose we respond to is a tragedy that didn’t have to happen.”

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine, is at the center of this storm. It’s often mixed — without the user’s knowledge — with other drugs like heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana or pressed into counterfeit pills resembling Xanax or Oxycodone. Just two milligrams — the equivalent of a few grains of salt — can kill.

“You don’t have to specifically be a fentanyl addict,” Patton says. “You just have to be unlucky.”

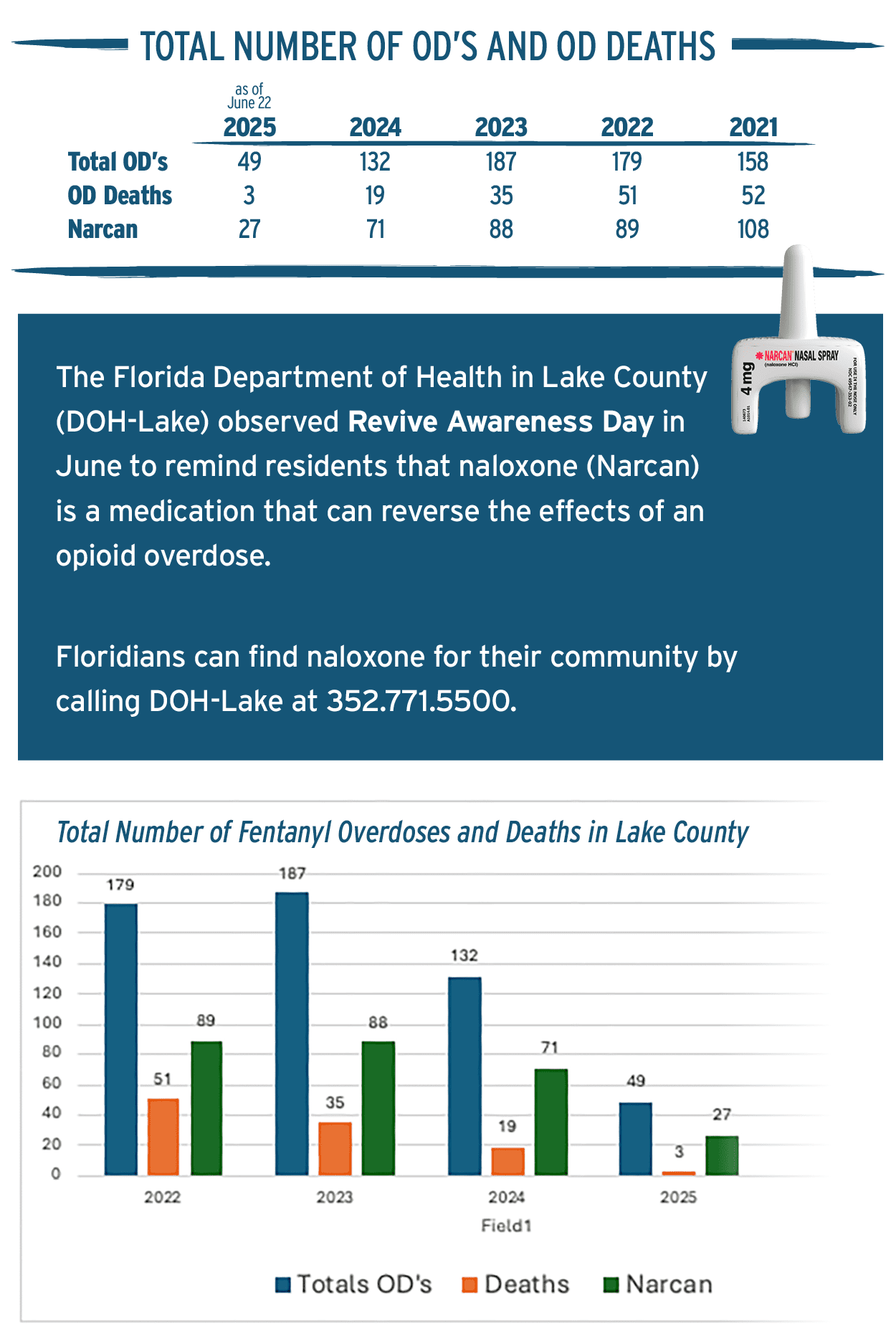

Lake County saw 52 fatal overdoses in 2021. By 2023, that number dropped to 19. So far in 2025 (from January 1-June 22) there were three confirmed overdose deaths.

Patton and his team hope that trend continues, but they’re not letting their guard down.

“Every call we respond to is a chance to save a life,” he says. “We’re seeing people of all ages. Teenagers, grandparents, parents; no one is immune.”

Lake County deputies now carry Narcan (naloxone), a fast-acting medication that can reverse an opioid overdose when sprayed into the nose. Every deputy is trained to administer it to civilians, themselves or each other in case of accidental exposure.

That training has saved lives … including the life of a deputy who collapsed after a traffic stop.

The deputy wore gloves while patting down the suspect, who was suspected of using or transporting narcotics, but it wasn’t enough. After securing the suspect in his patrol car and removing his gloves, the officer either inhaled fentanyl residue or had it on his clothes or hands.

“He started having trouble breathing and said he felt faint,” Patton says. Other deputies promptly administered Narcan. It took three doses — one on the spot, one on the way and one at the hospital — but he survived.

The threat is so severe that even the department’s K9s are trained to detect fentanyl — in trace amounts because dogs aren’t immune to its effects.

“I spoke to one our handlers and he said the dogs would have the same symptoms as humans and they would use the Narcan on them as they would a human,” Patton says.

Lake County Sheriff Peyton Grinnell has made fentanyl enforcement a top priority by focusing efforts on dismantling mid- to high-level trafficking operations. The sheriff’s narcotics task force has seized more than 50 pounds of dangerous drugs in the past two years through partnerships with federal agencies like the DEA, FBI and HSI and police departments in Clermont, Leesburg, Eustis and Mount Dora.

“Sheriff Grinnell’s mission is clear: protect our community and protect our deputies,” Patton says.

That protection includes supplying deputies with free Narcan through Florida’s Helping Emergency Responders Obtain Support (HEROS), program which has distributed more than 850,000 doses statewide since its inception.

The impact has been great in Lake County. According to Patton, fentanyl deaths have dropped dramatically due to rapid response by trained deputies and easier community access to Narcan, which is now available over the counter.

“People can get it from their pharmacy. You can keep it in your glove box, your purse, anywhere,” he says. “You might never need it, but if you do, you’ll be grateful you had it.”

Still, the danger, silent and merciless, persists.

Fentanyl comes in powders, pills and even liquid form. It’s been found in nasal sprays, eye drops, paper or candy. Because it’s cheap to manufacture and incredibly potent, traffickers use it to stretch or replace other drugs despite the potential for deadly consequences.

“You think you’re taking a Xanax or smoking marijuana and don’t know it’s been contaminated. You’ll never know until it’s too late,” Patton says.

That’s what makes this drug different and more dangerous.

Even as national trends show signs of improvement, the crisis isn’t over. According to the DEA—information supplied by Patton—7 out of 10 pills tested in 2023 contained a potentially lethal dose of fentanyl. In 2024, that dropped slightly to 5 out of 10, still far too high.

Public health efforts are beginning to make a difference. Wider naloxone distribution, increased funding and access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) programs are helping. Policy changes have made it easier to obtain methadone and buprenorphine, key tools in treating opioid addiction and more and more centers or programs that offer support and treatment, are popping up throughout Florida, including Lake.

That’s why education is as important as enforcement, Patton says. He wants parents to talk to their kids. He wants young people to understand that today’s drugs are more deadly than they were 10 years ago.

“It’s not about experimenting anymore. Sometimes you don’t get a second chance,” Patton says.

Lake County has also sought justice through Florida’s “Death by Distribution” statute — a law allowing prosecutors to charge drug dealers with homicide if someone dies from drugs they supplied. Several cases like that have resulted in lengthy prison terms, including one recent 20-year sentence.

“This sends a clear message that you’ll be held accountable,” Patton says, adding that the department remains cautiously hopeful and determined to curb overdoses.

“We’ve made progress, but we’re not done,” he says. “Every life matters. If we can save one more son, one more daughter, one more parent, then we’ll keep fighting.”

A former addict and a local mentor join forces to stop fentanyl from stealing more lives

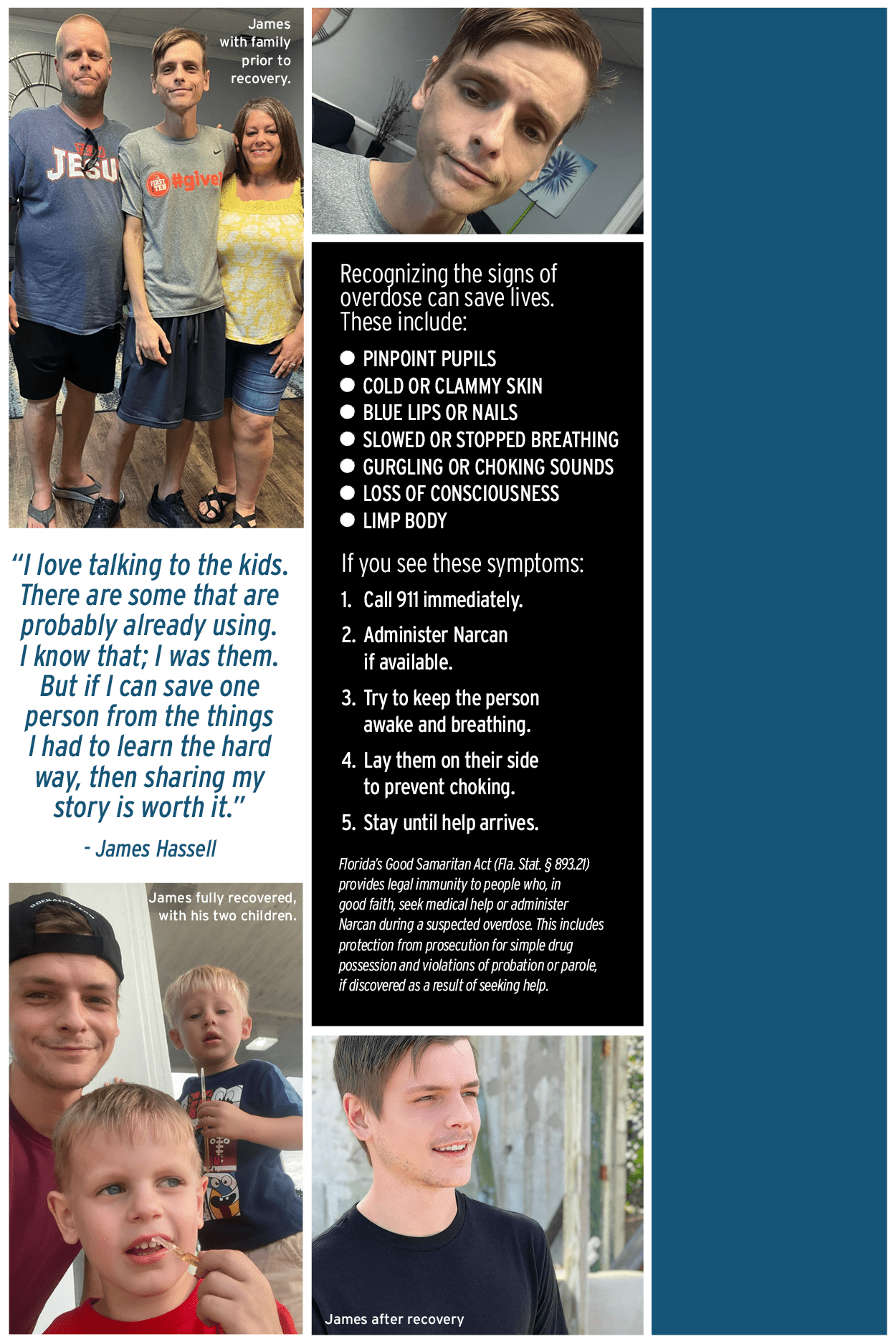

James Hassell doesn’t shy away from the truth — not in front of students and definitely not about himself.

“I was a scoundrel,” he says. “The essence of a dirtbag. I lied, I stole, I manipulated. I worked and every dime I made was going to drugs—whatever it took to get high.”

Today, James, 28, is nearly three years sober.

“I started using when I was 12 or 13 in middle school, and by 14 or 15 I was already addicted to pills, including Adderall from a cousin. My brain wasn’t even developed yet,” he says.

What followed was a downward spiral: marijuana, alcohol, prescription painkillers, heroin. Then came fentanyl—the synthetic opioid now fueling a national crisis.

“The first time I used it, I didn’t even know what it was,” James says. “A coworker pulled over and crushed up what I thought was cocaine. He said, ‘It’s fentanyl.’ I said, ‘All I hear is that this stuff kills people.’ He told me it only does if you do too much. I believed him.”

James was instantly hooked. Soon he was using daily—multiple times a day—often mixing fentanyl with Kratom, a plant-based drug he wrongly thought was safe. He thought he was saving money but eventually spent up to $400 a day chasing a high that never lasted.

“The high from fentanyl, especially when mixed with other drugs, floors you. It’s immediate, but short lived. You’re like asleep standing up you’re so high out of your mind,” he says. “There are TikTok videos out there of people like that, they call them ‘zombie people’ and I didn’t know I was doing that, but my family noticed. That’s when they knew something was really wrong.”

At his lowest, James weighed less than 100 pounds—he’d developed an eating disorder as a result of his drug use. He was wanted, found and luckily spared by a dealer he owed money to. He couldn’t hold a job. He forged a check in his mother’s name but after the bank called her, she gave him two options: jail or rehab.

“That was my second and last rehab. I was tired of so many bad things happening to me and I thought, ‘I guess I’m done.’ I put my faith in Jesus and it saved my life.”

He completed more than six months of inpatient and outpatient recovery, and this time, it worked.

Today, he shares custody of his two kids, he’s rebuilt relationships and is working on his health. He also helps teens through “Pathway to Purpose”—a 16-week mentorship and life skills course. It’s all part of the Powerhouse Youth Project, a program Executive Director Scott Chevalier introduced at Leesburg High School to equip students with tools and confidence to avoid drugs, violence and hopelessness and find their purpose.

Scott and James have teamed up to speak at Alee Academy and high schools in Leesburg, Umatilla, and South Lake during school-wide assemblies. James shares his darkest days and experiences in hopes of getting through to students about the dangers of doing drugs.

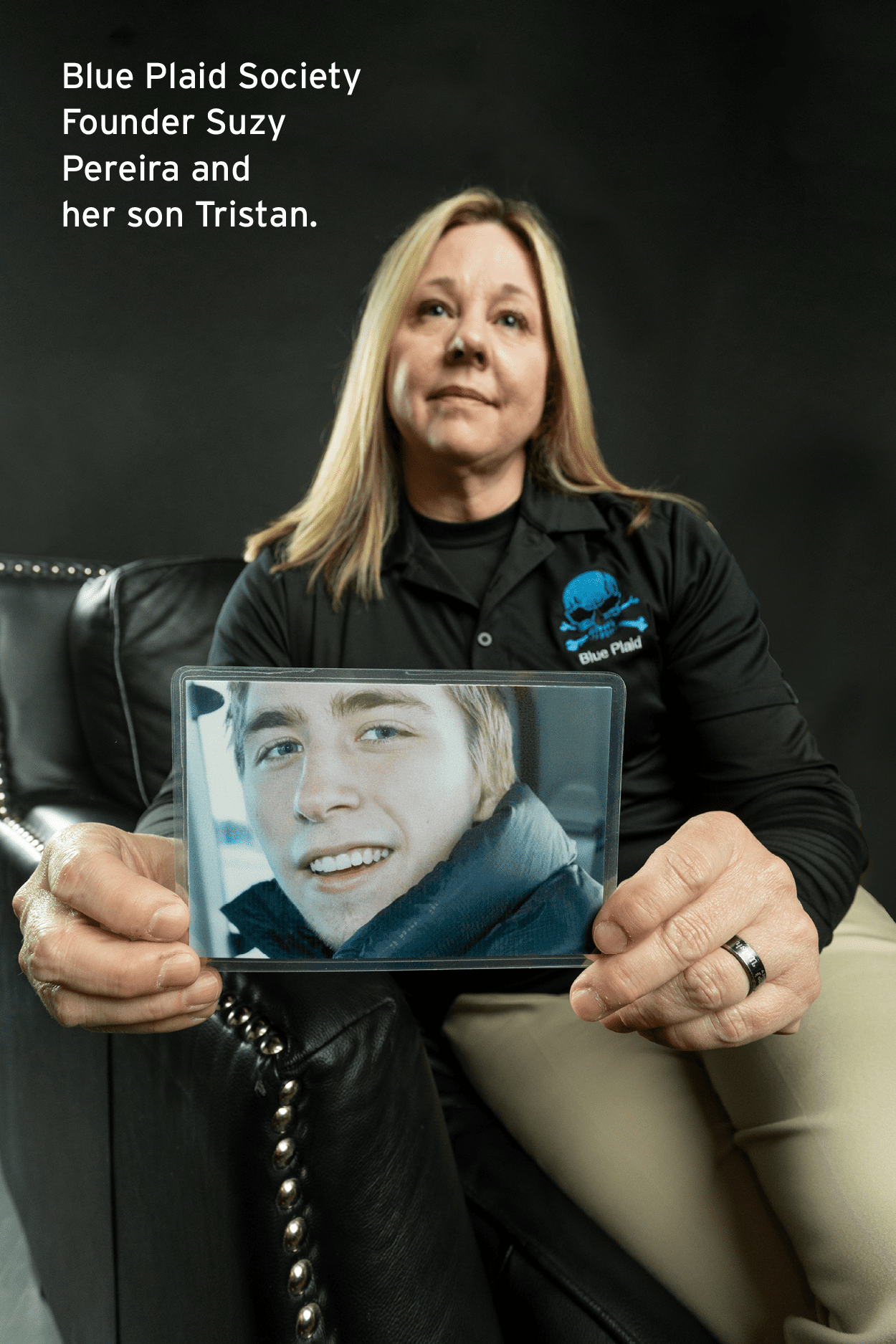

Scott’s mission expanded after hearing Blue Plaid Society Founder Suzy Pereira speak about losing her son Tristan to fentanyl poisoning. Tristan, an addict, didn’t realize the heroin he used was laced. Her nonprofit, named after the blue plaid shirts Tristan loved, aimed to raise awareness about hidden fentanyl dangers.

Later, when Suzy stepped back due to health issues, Scott stepped in—bringing Suzy’s senior peer prevention specialist James with him to keep the message alive.

“We couldn’t let it end,” Scott says. “This is life and death. Teens are getting pills off Snapchat, weed laced with fentanyl—they have no idea what they’re playing with.”

The program isn’t about scare tactics. Scott and his team, including mentors like James, focus on real conversations, helping kids set meaningful goals and building emotional resilience—like learning how to handle life’s challenges, knowing it’s okay to feel what they feel, but then to ask for help when they need it.

“When James walks in, the room changes,” Scott says. “He’s real. He’s lived what they’re facing and he doesn’t sugarcoat things. They can relate to him.”

“I love talking to the kids,” he says. “There are some that are probably already using. I know that; I was them. But if I can save one person from the things I had to learn the hard way, then sharing my story is worth it.”

When students ask if he still craves drugs, James is honest. “I did at one time and I tried Kratom once after rehab, and it did nothing for me. I don’t want any of that anymore,” he says.

He also admits it’s not always easy to revisit the past.

“Sometimes, it’s like I’m reliving some of the darkest times in my life. It’s hard but I get through it because I know I’m OK now.”

He also knows he could’ve died.

“It’s surreal to look back and realize I was doing the exact thing that’s killing over tens of thousands of Americans every year,” he says. “That could’ve been me.”

James says the things he feels the most shame from is how he felt about his kids, but then he pauses, and sees it was kind of a godsend.

“My ex would try and get me to see I was missing out on my kids when I was using, but I didn’t want the burden of taking care of them,” he says. “I feel bad about it, but I’m glad their mom made the choices she did when it came to not leaving them alone with me because I could’ve put them in danger. I’m grateful for where I am now and that I can be a good dad to them.”

His message to students is simple yet hard-hitting: “You matter. It’s OK to not be OK but just don’t give up on yourself, especially by letting drugs take over your life.”

If any Lake County school would like this message shared on their campus to students, please email Powerhouse Youth Project at scott@powerhouse.org. For more information, visit www.powerhouse.org.

Photos: Nicole Hamel

Originally from Nogales, Arizona, Roxanne worked in the customer service industry while practicing freelance writing for years. She came on board with Akers Media in July 2020 as a full-time staff writer for Lake & Sumter Style Magazine and was promoted to Managing Editor in October 2023—her dream job come true. Prior to that and after just having moved to Florida in 1999, Roxanne had re-directed her prior career path to focus more on journalism and went on to become a reporter for The Daily Commercial/South Lake Press newspapers for 16 years. Additionally, Roxanne—now an award-winning journalist recognized by the Florida Press Club and the Florida chapter of The Society of Professional Journalism—continues working toward her secondary goal of becoming a published author of children’s books.