By Gary Corsair

The loneliest man

The short life and untimely death of a NASA whistleblower.

Neil Armstrong would never have declared “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” on July 20, 1969 if fellow astronaut Roger Chaffee hadn’t shouted, “We’ve got a bad fire! Let’s get out! We’re burning up! We’re on fire!” 30 months earlier.

Those horrific exclamations at 6:31 p.m. on January 27, 1967 were Roger’s last words. He died 17 seconds later alongside Apollo 1 crewmates Virgil “Gus” Grissom and Ed White, trapped in a space capsule atop a Saturn 1B launcher. All three had their lungs charred by toxic fumes.

That fatal inferno led to widespread improvements in equipment and procedures that ensured a safe, 237,700-mile flight to the moon for Armstrong and the Apollo 11 crew.

“Apollo 1 tragically cost three lives, but I think it saved more than three lives later. Without it, very likely we would’ve not landed on the moon by the end of the decade,” Apollo 11 Commander Michael Collins told an interviewer.

Photo of the Apollo I capsule and the astronauts: Courtesy of NASA.gov.

The conclusion that three astronauts gave their lives so others could live has become part of NASA folklore. Left unsaid is that the Apollo 1 spacemen wouldn’t have died if NASA officials had heeded warnings voiced by Thomas Ronald Baron, a safety inspector for the company that built the space capsule/death trap White, Chaffee, and Grissom perished in.

In December 1966, Baron told a space agency employee, “Something has to be done. Someone is going to get killed.” On January 26, 1967, Baron told a newspaper editor, “I fear for the lives of the astronauts.” The next day, White, Chaffee and Grissom were incinerated in the very spacecraft Baron inspected and deemed unsafe.

Baron reached that alarming conclusion after observing and reporting poor safety practices, shoddy workmanship, accidents, overheating equipment, fluid leaks, altered specs, and damaged/defective parts. Among the most serious safety lapses: employees drinking on the job, technicians unfamiliar with equipment, a fire started by a welder, and a tank damaged when a worker fell on it.

Supervisors who initially praised Baron’s thoroughness became annoyed with his fault-finding. North American Aviation fired him on Jan. 5, 1967.

Baron promptly delivered 55 pages of concerns to NASA in hopes the Apollo 1 launch would be postponed until safety concerns were addressed. NASA reviewed the report, interviewed Baron, and dismissed his complaints as “hunches.”

Unbeknownst to Baron, Apollo 1 Commander Gus Grissom was also concerned. “There are a lot of things wrong with this spacecraft,” Grissom declared. “It’s not as good as the ones [Mercury and Gemini] we flew earlier. There’s something different about this thing.”

Grissom had reason to be wary. Apollo 1 had undergone 740 engineering changes… and the space capsule still wasn’t ready with liftoff just 36 days away.

(18 Oct. 1966) — The Apollo 1 prime crewmembers for the first manned Apollo Mission (204) prepare to enter their spacecraft inside the altitude chamber at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC). Entering the hatch is astronaut Virgil I. Grissom, commander; behind him is astronaut Roger B. Chaffee, lunar module pilot; standing at the left with chamber technicians is astronaut Edward H. White II, command module pilot. Courtesy of NASA.gov.

Despite misgivings, Grissom climbed into Apollo 1 for a launch simulation. Eight hours later, he and his crew suffocated in a 1,000-degree Fahrenheit inferno.

The next day, reporters who had dismissed Baron as a “crank” clamored to hear how he knew tragedy was inevitable.

Meanwhile, NASA moved decisively to reassure Washington politicians that space exploration must continue. Hundreds of millions of dollars in funding were at stake. Some lawmakers wanted the space program discontinued.

Within 24 hours of the fire, NASA convened the Apollo 204 Review Board – an 8-member panel that included six NASA executives – to investigate the tragedy.

More than 40 “witnesses” were interviewed. By the time Baron testified, his 55-page report had grown to 276 pages. Apollo program employees had been secretly feeding information to Baron since his termination by North American Aviation.

The review board found that “the test conditions were extremely hazardous… deficiencies existed in Command Module design, workmanship, and quality control” – exactly what Baron had been shouting for months. The board did not, however, determine the cause of the fire. And it did not validate Baron and his report.

Baron’s former employer was more forthcoming. The “Titusville Star-Advocate” reported that North American Aviation officials “agree that Baron’s allegations are, for the most part, true, but that the problems and discrepancies noted by Baron have since been cleared up.”

The non-finding of the review board didn’t sit well with politicians who controlled NASA’s funding. Congressman Donald Rumsfeld railed, “I am deeply disturbed by the report of the Apollo 204 Review Board … the Board failed to examine, or at least report on, the fundamental conditions which permitted the accident to occur …”

(1961) — Astronaut Virgil I. Grissom. Courtesy of NASA.gov.

On February 27, the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences convened a congressional hearing to find answers NASA couldn’t (wouldn’t?) produce.

Baron was called, but his long-awaited testimony was vague and devoid of details. Baron was clearly nervous. He seemed to be protecting someone. He was – North American Aviation electronics technician Mervin Holmberg, who told Baron he knew what caused the Apollo 1 tragedy. Subcommittee members insisted Baron identify his informant. With great reluctance, he named Holmberg. To Baron’s surprise, the committee called Holmberg. As Holmberg entered the room, Baron realized he’d been set up, that he was about to be discredited. Sure enough, Holmberg denied telling Baron anything.

In closing, Baron offered his report, now 500 pages, into evidence. Chairman Olin Teague declined, saying, “No thank you. Then we’d have to print it, which would be quite expensive.” Baron was flabbergasted. How could the committee turn down first-person documentation of problems within the space program?

Discouraged, ill (a severe case of diabetes), unemployed, and broke with a wife and two young children to support, Baron continued gathering information about unsafe practices at North American Aviation. Why? Baron explained, “It could happen again, unless someone makes sure things have changed in the space program.”

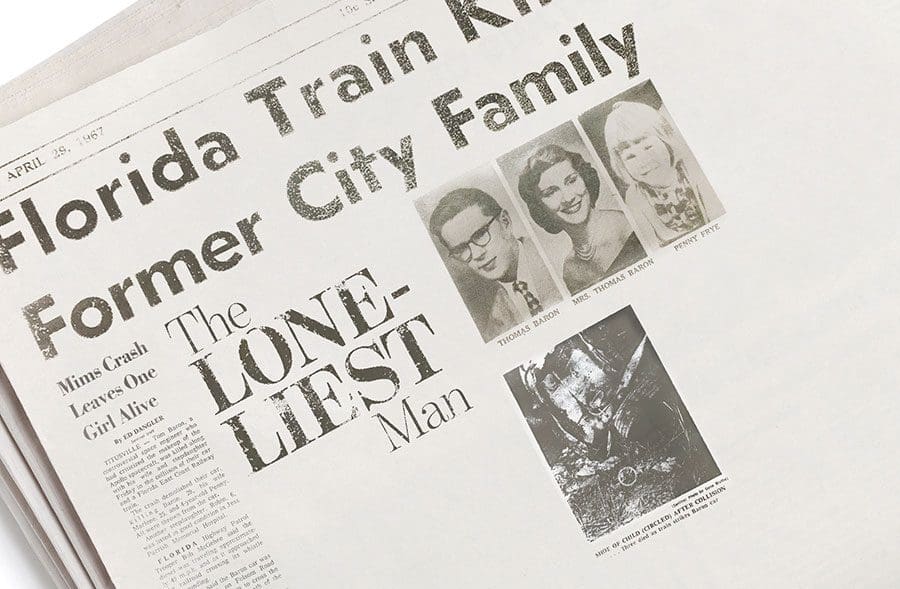

NASA was already making wholesale changes, but Baron didn’t live to see reforms he had advocated. Seven days after testifying before the Congressional committee, the “Star-Advocate” reported: “Apollo Critic, Wife And Child Killed in Wreck. A man who spent the last few months in a race against death – the death of astronauts, lost a race against death Friday night when his car collided with a Florida East Coast Railway switch engine in Mims.”

Fifty-four years later, speculation persists that the car/train collision was, in fact, murder.

With its most vocal critic forever silenced, NASA resumed its quest to put a man on the moon.

Today, Chaffee, Grissom and White are memorialized in a Kennedy Space Center exhibit. There are no monuments to Tom Baron.

We still don’t know who Thomas Ronald Baron was, what he knew, or why he died. To find the answers we must return to Launchpad 34. Baron was a nobody – and would have remained an unknown if Chaffee hadn’t shouted, “We’re on fire!”

Virgil I. Grissom, command pilot; Edward H. White II, senior pilot; and Roger B. Chaffee, pilot.

Why did astronauts Chaffee, Grissom and White die?

On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy doomed the Apollo mission when he told Congress: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth.”

The goal was, quite simply, unrealistic.

By 1966, space agency officials realized they couldn’t reach the moon before the end of the 60s…unless they cut some serious corners. “… It was obvious to me that we weren’t going to be able to land on the moon in the decade or even come close to it if we kept proceeding in the same sort of plodding way,” NASA Deputy Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr. admitted.

NASA decided to forgo testing Apollo one stage at a time, the way it had readied Mercury, and then Gemini. The Apollo launch, in effect, would be the test, like a baseball player going from first to home and bypassing second and third base.

Spacecraft propulsion researchers at the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center were “absolutely aghast.” Seamans recalled, “They said, ‘It will never work.’ But the idea was simple. It was, if you’re going to go through the exercise and the hundreds of millions of dollars to test the first stage, you might as well put everything else on top of it.”

Simple idea. Disastrous results. The Marshall Space Flight Center rocketry experts were right. The “all systems go” approach didn’t work.

Thomas Baron

Who was Thomas Baron, and what did he know?

One reporter called Baron “strange,” another remembered the 28-year-old as “intense.” A co-worker portrayed Baron as “way out there.” His ex-wife says he was “extremely intelligent.” They were all correct.

Baron was many things. Above all, he was a perfectionist.

The son of a Pennsylvania locksmith found his niche working on the Hound Dog missile program at Eglin Air Force Base in the Florida Panhandle, then parlayed his Air Force training into a job as safety inspector at North American Aviation. Baron loved his job, even though he worked long, pressure-filled hours as NAA scrambled to finish the Apollo 1 space capsule.

Curious facts lend credence to a foul play scenario:

- The train Baron struck had been dispatched from a NASA facility.

- Baron’s 500-page report hasn’t been seen since his demise.

- Baron told a family member he had been threatened and followed.

- Someone entered and ransacked Baron’s home prior to the crash.

- One of Baron’s neighbors saw “two men in dark suits” searching Baron’s trailer the night he died.

- All three victims had skull fractures. Were those fatal injuries consistent with a car driven at 30 mph clipping a train reversing at 40 mph?

Why did Baron die?

Baron attempted to drive his beloved 1959 Volvo across railroad tracks at a crossing 7/10ths of a mile from the trailer he rented outside Mims, Florida.

The Volvo was estimated to be traveling at 30 mph when it made a 90-degree turn into the crossing, struck the rear coupler of a reversing train consisting of only an engine and a gondola car, estimated to be moving at 40-45 mph. The train pushed Baron’s car 30 feet, off the tracks, and the Volvo tumbled end over end, ejecting three of the four occupants, and landing on Baron.

The train conductor said he blew his whistle before impact. Alleged witness Linda Sue Mullens, who was traveling in the opposite direction as Baron, and passed him moments before the crash, said she honked her horn to warn the driver of the Volvo. Another witness, a man, refused to make a statement to the investigating Florida Highway Patrol troopers.

The FHP accident report states that the crash was an accident. But some things don’t add up. For one, why would he try to beat a train that was only one car long? Baron was cautious and extremely safety conscious. He was no daredevil. And he wouldn’t have risked the lives of his wife and her two children.

NASA critic/author Bill Kaysing proposed a more sinister scenario. “I believe that Thomas Ronald Baron was murdered because he had the truth to tell about the Apollo project,” Kaysing stated.

Was Baron silenced because he wouldn’t stop talking about shortcomings in the space program? If so, how did his murderer(s) arrange the car/train accident? And what about the lone eyewitness, Linda Sue Mullins? Little is known about her except for the fact that she lived in a home owned by North American Aviation, Baron’s former employer.

Some have suggested that Baron committed suicide. If so, would he have taken his family with him? The fact that Baron hoped to turn his 500-page report into a book also suggests that he wanted to live.

Did Thomas Ronald Baron possess proof that negligence led to the death of three astronauts? What became of his 500-page report? Was he silenced because he knew too much? The answers to those questions remain as elusive today as they did 54 years ago.

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

Gary Corsair began writing professionally while attending high school in Greentown, Indiana. He's spent most of the past 46 years in writing, reporting, editing and producing roles for newspapers, magazines, TV, and radio. He's served as publisher and editor of three newspapers, TV news director, and executive producer of two documentaries about The Groveland Four. Gary’s earned more than 65 awards for journalism excellence.

Intersting article!

Could you provide some specifics on the newspaper article?

I ‘d like to know the name of the newspaper and the date of the article; the date appears to be April 28 or 29

Can you supply some sources here? How did you dig up some of these details?