By Gary Corsair

Adoption is Third and Final Option for Many Foster Kids

Adoption is third and final option for many foster kids

In a better world, children of troubled parents would spend months not years in foster care, and then return home and live happily ever after when moms and dads get their act together.

Paying strangers to take in abused and/or neglected kids isn’t supposed to be a long-term arrangement. Foster care should be a detour; a safe harbor for children removed from dysfunctional families until mom and dad replace neglect with nurturing.

Unfortunately, that scenario is a fairy tale.

Most foster children get passed around like hot potatoes, forced to spend years in a Dept. of Children and Families (DCF) system that desperately needs foster parents, additional case workers, and more resources.

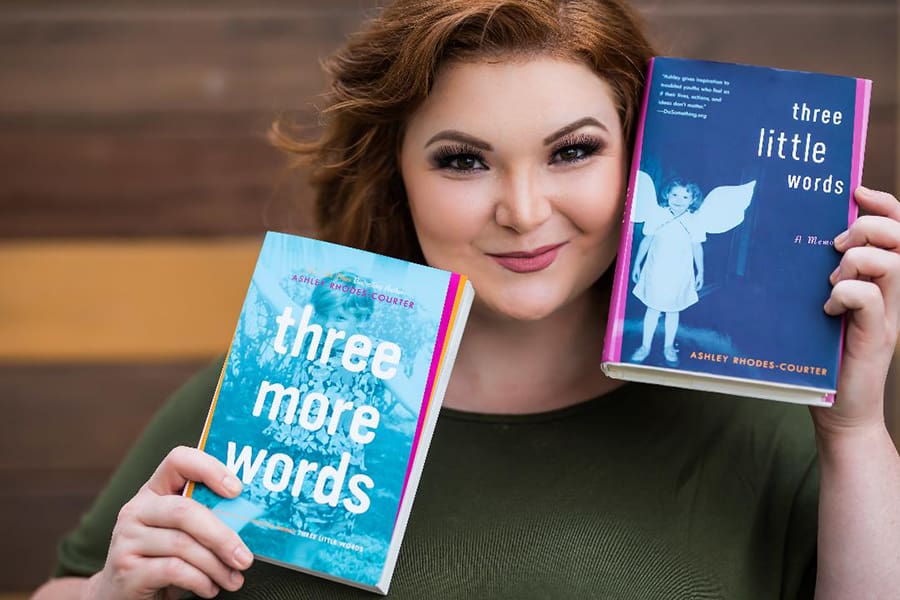

Ashley Rhoades-Courter lived in 14 foster homes before being adopted at age 12 by Crystal River couple Philip and Gay Courter.

“Moves happen for a wide variety of reasons,” Ashley said. “Homes open or close routinely, or foster parents may even get into trouble. Some placements are meant to be temporary; others more long-term. A parent can make a phone call and request a child be removed whenever they’d like.”

Unfortunately, foster children are unable to extricate themselves from bad situations with a phone call.

“There is such a shortage of homes and caseworkers that children fall through the cracks,” Ashley said. “One foster home had 16 kids, sharing two bedrooms in a trailer. We were beaten, starved, locked outside, and subjected to horrific tortures. These foster parents had the community fooled and even took foster parent training classes. They were considered to be saintly for taking ‘kids that nobody else would.’”

“When I think back to some of the foster homes Ashley was in, it’s amazing she’s such a well-adjusted, successful adult,” Philip says.

Unfortunately, Ashley’s foster care experience is typical. In Florida, a foster child is placed 5.86 times every three years before they age out of the system at 18, are taken in by a relative, adopted, or return to their biological parents.

Getting a family safely back together is almost always the first goal when it comes to families and the best interests of a child. Unfortunately, half of the children removed never return home.

Biological parents have no hope of being reunited with their child unless they complete a case plan to satisfaction of a court.

“The case plan is like probation,” says Susan, who became a child welfare attorney in Vero Beach. “The case plan requires that you see your kids once a week, get a job, support yourself, do all the treatments you’re supposed to do. It’s overwhelming.”

The reunification process is also extremely time consuming. A child’s home life can turn terrible in an instant, but the fix takes months, even years.

In too many instances, the parents are so busy trying to meet the terms of their “probation” that they neglect visiting the very children they are trying to regain. Invariably, the chasm between child and parents widens.

“When we remove people from their homes and people who care about them, the system does not always do a good job of keeping them connected to those people,” Rosenberg said.

Susan knows. She worked as a DCF investigator before attending law school and becoming a foster child advocate.

“A case plan is not supposed to take more than 12 months in most states, but sadly, children do linger in care far longer than is healthy,” Ashley states.

“When children are put in foster care it’s supposed to be temporary, they’re supposed to have frequent visitation with their parents, they’re supposed to have frequent visitation with their siblings, they’re supposed to be placed together. But the truth of the matter is those placements aren’t always possible. And it’s not always possible for the department to facilitate those visits,” Susan says.

Most parents don’t turn their lives around. Their drug habit is too deeply ingrained. They can’t get rid of the loser boyfriend. They can’t keep a job. They are never reunited with their child.

“If you don’t complete your case plan it goes to the next step, which is termination of parental rights. Most parents start case plans but don’t finish,” says Lake County resident Jamie Abbott, who has fostered 31 children and adopted three of them over the past 15 years.

“Out of my 31, most didn’t complete the case plan, they end up going with grandparents or aunt and uncle, sometimes even out of state,” Jamie said.

Some parents beat the odds and complete case plans, only to return to behaviors harmful to the child. “Sometimes parents do get them back, but six months later the child is back in foster care. I’ve noticed that. That has been a trend,” Jamie said.

Reunification is a most elusive goal.

When reunification is finally ruled out, child welfare workers shift gears and look for blood relatives willing to take the child. Plan B – “permanency” through “kinship care” – has a 60% success rate.

That brings us to Plan C: Adoption.

DCF has removed many of the hurdles associated with private adoptions in a concerted effort to move children out of a foster care system bursting at the seams.

“When you’re working with the Department, they pay for everything. The cost of adoption is free,” Susan says. “When you become an adoptive parent with the Department you go get your level 2 fingerprints, you do your letters of recommendation, you do your MAPP (Model Approach to Partnerships in Parenting) classes, which are foster care trainings — and then you get the child and are able to adopt.’

No money out of pocket, when private adoptions cost as much as $30,000?!!

“It’s free. It doesn’t cost you a penny,” Jamie confirms.

And that’s only one incentive.

Foster parents receive a monthly subsidy.

There’s also an adoption subsidy. Adoptive parent training class and required home study are provided free of charge. Court costs and fees can be paid by a community-based agency if the family cannot afford them.

But wait, there’s more.

Children adopted from foster care are eligible for free tuition at any Florida state university, community college or vocational school. The federal adoption tax credit has been raised to $13,400 per child. And children are eligible to receive health care through the Medicaid until age 18.

Sounds too good to be true, right? It is.

DCF’s adoptable kids are damaged. Almost all have disabilities, medical conditions and/or mental, physical or emotional handicaps.

That’s why people with love to give aren’t beating down DCF’s door. In Circuit 5 (Lake, Sumter, Marion, Citrus and Hernando counties) only 127 of 256 (49 percent) foster children eligible for adoption were adopted in the first half of 2022.

“The emotional toll of a former foster child is significant,” Ashley said. “Most of my former foster brothers and sisters have experienced homelessness, unemployment, drug abuse, have criminal records, become teen parents or have lost custody of their own children. The outcomes for foster children are bleak. My own brother died of a drug overdose in his 20s. It’s hard to have dreams or aspirations when you’re in constant survival mode, but I was too stubborn to be the failure everyone expected me to be. I was also very lucky to have not been born drug affected or to live with a learning disability.”

Many prospective foster parents will only consider adopting infants. But babies are often a roll of the dice.

“Drugs are a huge thing,” Jamie says. “My foster daughter was born so drug addicted that she had to be on morphine. The nurse in Leesburg said she shook so bad they had to put her on anti-seizure medication. They finally weaned her off at 5½ weeks.”

Teenagers aren’t on the top of many want lists even though most teens desperately want to be adopted and are determined to make the most of their ticket out of foster care.

Ashley was certainly motivated to leave the system.

“Ashley saw moving in with us as a good business deal, as it were,” Philip says. “She thought, ‘If I stay in foster care the chances of me going to college and having a career are not as good if I stay in foster care.’ She was smart enough to say, ‘I better not screw this up.’”

And she didn’t. “Adopting Ashley was the best thing we did with our lives,” Philip remarked. “She’s so smart, and she’s so capable.”

That’s not to say that adding a 12-year-old to the Courter family was a breeze.

“It took over probably three years to gain her trust. It was a slow process, and an extremely stressful process,” Philip remarked. “I was probably the first father figure in her life that treated her well. My wife was her 14th mom, and she hated a lot of these women.”

Ashley was fortunate. Not every adoptive parent rides out the storm.

“I had adopted parents to support me if I needed anything, but that isn’t always the case. Sometimes adoptive parents aren’t able to support the child anymore,” says Maria Batista, statewide coordinator for Florida Youth SHINE.

“You get these individuals left with the real responsibilities of parenting of – I don’t want to say damaged children, because I don’t believe in that – but children with trauma. And a lot of that trauma is unhealed and unaddressed, and they hit a certain point where those children need more intensive services and they don’t know where to turn. They may not have private insurance, they’re just kind of out of luck.”

Adoption should be the happy ending. But it isn’t always. Nearly 10% of foster children who move into a “permanent home” are returned to foster care within a year.

Why? Primarily two reasons: the new child isn’t considered a good fit with the family; or adoptive parents are overwhelmed by the physical or emotional needs of the adopted child.

“My advice to anyone considering fostering would be to become trauma informed. Think carefully about your family situation and how a new child with extra needs will be able to get the support they need. Think about what works best for your stage of life,” says Jenny Lewis, a Sarasota native who, with husband Tripp, has had nine full-time placements. “Don’t make decisions out of guilt but do consider how you can give of yourself to love a child in need.”

Sadly, some foster and adoptive parents decide they aren’t cut out to take a stranger into their home.

Susan Chesnutt lived the trauma of being accepted, and then rejected.

“They had called me their child, but one day I came home and my stuff was bagged up in trash bags, just like it was every other time I got kicked around as a foster child. Two big contractor trash bags. No backpack, no nothing. It was devastating for me . . . when that fell apart, that was one of the hardest things I’ve ever dealt with in my entire life because I finally felt like I was finally part of another family.”

“I wasn’t having sex, I wasn’t using drugs, I was getting all these accolades, but I was also this damaged little girl,” Susan said. “I was trying my best, and so were they, but I was apparently starting to have an affect on their small children. With that dynamic in the home, they had to make a decision for their family. I don’t blame them for that. Sometimes you bring someone in, and it doesn’t work the way you hoped it will.”

More often than not, adoptions fall apart because the child is more damaged than the new parents realized.

“It is a difficult journey, and you will hear heartbreaking stories. You will feel frustrated from the ‘system.’ Things don’t always go the way you think they should for these children,” Jenny says. “These children often have difficult behaviors and a high level of care because of what they’ve been through. We’ve had teens struggle with bedwetting, babies being weaned from drugs, toddlers with severe speech delays, and of course the huge emotional trauma these kids have experienced.”

The rewards are great for those willing to endure a year or two of jumping through hoops.

There’s nothing quick about the process. Biological parents of foster kids are given plenty of time to straighten out before they are given another chance or are stripped of their parental rights.

“Sometimes appeals slow things down, sometimes parents get long case plans that drag on past the 12 months of permanency,” Susan said. “It can be real quick, too, I’ve seen it happen in less than a year multiple times over the years. If parents consent early on to termination (of parental rights) that definitely helps speed up the process.”

And yes, six months is considered quick.

Of the 38 Lake County children adopted after being removed from October 2021 thru September 2022, only six were adopted within 24 months. Thirty were in foster care for 24-48 months before being adopted.

“By the time an adoption is finalized, the participants in this play have been on stage now for two to two-and-a-half years,” Susan says. “You have case managers and guardian ad litems that come out to your house every single month, you’ve got judicial reviews every five or six months, you’ve got all these medical assessments, and this and a third. It’s a very overwhelming part of the process. By the time these adoptive parents get to the end they really do want DCF to take off and they don’t want to deal with them anymore.”

Adopting a foster child may not be a walk in the park, but the upside of providing love and stability to a damaged child is huge.

“The best is taking that child that has suffered abuse — whatever type of abuse — and welcoming that child into your home and seeing the difference the safety and security makes and how it feels over time and the love,” Jamie said. “When they stop being so clammed up, start being more open. That is the most rewarding thing, seeing your influence on that child.”

Gary Corsair began writing professionally while attending high school in Greentown, Indiana. He's spent most of the past 46 years in writing, reporting, editing and producing roles for newspapers, magazines, TV, and radio. He's served as publisher and editor of three newspapers, TV news director, and executive producer of two documentaries about The Groveland Four. Gary’s earned more than 65 awards for journalism excellence.